How an over-worked baker, the US Navy and the infamous “executive’s wife” helped create the greatest KitchenAid ever

Herbert Johnston, an engineer at the Hobart Manufacturing Company was a curious man, or rather he was a man who was constantly curious. He was one of that band of engineers who want to use their practical skills to solve other people’s problems.

So, when in 1908 he saw an over-worked baker working away to mix bread dough with nothing but an iron spoon and brute force, he thought that there must be a better and more efficient way of doing it.

It took him nearly seven years to develop an 80-quart electrical stand mixer but when it was introduced sales grew rapidly, saving bakers’ arms up and down the country. It came to the notice of the procurement department of the US Navy and they ordered mixers for two new Tennessee-class battleships, the California and the Tennessee, as well as the U.S. Navy’s first dreadnought battleship, the South Carolina. By 1917, the stand mixer had become “regular equipment” on all U.S. Navy ships.

It took him nearly seven years to develop an 80-quart electrical stand mixer but when it was introduced sales grew rapidly, saving bakers’ arms up and down the country. It came to the notice of the procurement department of the US Navy and they ordered mixers for two new Tennessee-class battleships, the California and the Tennessee, as well as the U.S. Navy’s first dreadnought battleship, the South Carolina. By 1917, the stand mixer had become “regular equipment” on all U.S. Navy ships.

The product’s overwhelming success prompted Johnson and the other Hobart engineers to think about the potential for a smaller model that might be used in the home kitchens. World War I interfered, and while the battleships benefited from the mixers, the American public had to wait until peacetime returned.

It wasn’t until 1919 that the Model H-5, the first stand mixer for the home, was introduced. It came not only with an array of attachments, but with a new brand name too. According to the brand’s official history the name was given to it but one of the Hobart executive’s wives whom having tried a prototype, is supposed to have exclaimed, “I don’t care what you call it, but I know it’s the best kitchen aid I’ve ever had!”

The KitchenAid trademark was quickly registered with the U.S. Patent Office.

The H-5 was also the first in what was to be a long line of KitchenAid stand mixers that utilized a “planetary action,” a revolutionary design that rotated the beater in one direction while moving it around the bowl in the opposite path.

It wasn’t a small unit though, standing about 26 inches (33cm) high and weighing approximately 65 pounds (29.5kg).

Many retailers were initially hesitant to carry the unique product so the company turned to its own largely female sales force, who set out to sell the 65-pound H-5 door to door. They gave in-home demonstrations to groups of women demonstrating how the machine could mix, beat, cut, cream, slice, chop, grind, strain, and freeze and sales quickly grew.

In 1927 the Model G stand mixer was introduced. Lighter and more compact than the H-5, it sells 20,000 units in its first three years on the market. Early adopters of the Model G included John Barrymore, Henry Ford, and Ginger Rogers

Then in the 1930s the company hired Egmont Arens to design three new, more affordable stand mixer models. Arens was the Art Editor of Vanity Fair, as well as being a world-renowned artist, designer, and “industrial humaneer” championing a consumer-centric approach to product design and packaging.

His client list included G.E., Fairchild Aircraft, and the General American Transportation Company and indeed the Hobart company for whom he had designed a meat slicer.

Arens’ design for the 4½-quart-capacity Model K45 was sleek and modernistic, far ahead of its time. It remains virtually unchanged to this day. It was released in 1937 to huge success. All KitchenAid components are compatible with the front attachment hub of every mixer made since that day.

Arens’ design for the 4½-quart-capacity Model K45 was sleek and modernistic, far ahead of its time. It remains virtually unchanged to this day. It was released in 1937 to huge success. All KitchenAid components are compatible with the front attachment hub of every mixer made since that day.

One final and famous innovation wasn’t actually introduced till 1955, when at the Atlantic City Housewares Show, KitchenAid unveiled a range of colours including Petal Pink, Sunny Yellow, Island Green, Satin Chrome, and Antique Copper.

So if you are like Herbert Johnston, and are naturally curious and you had ever wondered about the origins of your KitchenAid, now you know.

In 1974, when Alan retired, his three sons, Sam, Martin and Julian Rayner, took over the business.

In 1974, when Alan retired, his three sons, Sam, Martin and Julian Rayner, took over the business.

Strauss too could see the potential, and on May 20, 1873, US Patent No. 139,121 for “Improvements in fastening pocket openings” was issued in the name of Jacob W. Davis and Levi Strauss and Company.

Strauss too could see the potential, and on May 20, 1873, US Patent No. 139,121 for “Improvements in fastening pocket openings” was issued in the name of Jacob W. Davis and Levi Strauss and Company.

The next big change happened when Lipton went on “vacation” to Australia. In fact, he never planned on going to Australia, the story was a cover for a trip to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). There a recent blight had ruined the English coffee planters, and the survivors were now planting tea. With land prices low, Lipton had spotted another opportunity and bought five of the bankrupt plantations. This and his subsequent acquisition of about a further dozen sites allowed him to unveil a new slogan, “Direct from the Tea Gardens to the Teapot.”

The next big change happened when Lipton went on “vacation” to Australia. In fact, he never planned on going to Australia, the story was a cover for a trip to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). There a recent blight had ruined the English coffee planters, and the survivors were now planting tea. With land prices low, Lipton had spotted another opportunity and bought five of the bankrupt plantations. This and his subsequent acquisition of about a further dozen sites allowed him to unveil a new slogan, “Direct from the Tea Gardens to the Teapot.”

As the existing factory in Dehiwala was restricted in its capacity, the company opened a new biscuit factory at

As the existing factory in Dehiwala was restricted in its capacity, the company opened a new biscuit factory at  Mineka is now the president emeritus focused on quality improvements and innovation. He has set up other companies in confectionery, canning and hospitality. He has served as the chairman of the Southern Regional Economic Development Commission.

Mineka is now the president emeritus focused on quality improvements and innovation. He has set up other companies in confectionery, canning and hospitality. He has served as the chairman of the Southern Regional Economic Development Commission.

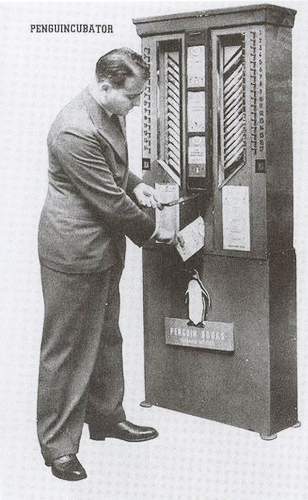

It was then that Mrs Prescott spotted the Agatha Christie Poirot Book “The Peculiar Affair at Styles” lying amongst the assorted titles spread around her husband’s meeting table. She enquired whether the firm was considering selling the softcover books, and announced that she would buy several a week if the price were sixpence or less.

It was then that Mrs Prescott spotted the Agatha Christie Poirot Book “The Peculiar Affair at Styles” lying amongst the assorted titles spread around her husband’s meeting table. She enquired whether the firm was considering selling the softcover books, and announced that she would buy several a week if the price were sixpence or less.

Incorporating his own experience of looking after young children and borrowing from another everyday piece of equipment, he used an innovative one-step umbrella-fold type construction. This easy-to-use functionality meant mothers could quickly fold the buggy with one hand, while holding baby in the other. It was to prove a godsend for parents.

Incorporating his own experience of looking after young children and borrowing from another everyday piece of equipment, he used an innovative one-step umbrella-fold type construction. This easy-to-use functionality meant mothers could quickly fold the buggy with one hand, while holding baby in the other. It was to prove a godsend for parents.

In 1856, Frederick, the youngest of three Schwarz brothers, emigrated to the U.S. from Germany, joining his brothers in Baltimore, Maryland. A few years later in 1862, the brothers opened ”Toy Bazaar” a specialist toy retailer.

In 1856, Frederick, the youngest of three Schwarz brothers, emigrated to the U.S. from Germany, joining his brothers in Baltimore, Maryland. A few years later in 1862, the brothers opened ”Toy Bazaar” a specialist toy retailer.

So Ben teamed up with a friend from college who was living in New York, Paul Sciarra and they came up with a product called Tote, which Ben describes as “a catalogue that was on the phone.”

So Ben teamed up with a friend from college who was living in New York, Paul Sciarra and they came up with a product called Tote, which Ben describes as “a catalogue that was on the phone.” While Tote was moderately successful Ben and Paul were developing another idea “I’d always thought that the things you collect say so much about who you are.” Ben says his childhood bug collection is really “Pinterest 1.0.”

While Tote was moderately successful Ben and Paul were developing another idea “I’d always thought that the things you collect say so much about who you are.” Ben says his childhood bug collection is really “Pinterest 1.0.”

And while the company sees itself as “the place to plan the most important projects in your life”, the brand’s mission “is not to keep you online, it’s to get you offline. Pinterest should inspire you to go out and do the things you love”

And while the company sees itself as “the place to plan the most important projects in your life”, the brand’s mission “is not to keep you online, it’s to get you offline. Pinterest should inspire you to go out and do the things you love”

However, the real reason was a completely different one. The BBC had decided that it wouldn’t play it because of the clear reference to “Coca-Cola”, which went against their “no product placement” policy.

However, the real reason was a completely different one. The BBC had decided that it wouldn’t play it because of the clear reference to “Coca-Cola”, which went against their “no product placement” policy. With a one-day gap in their schedule, Ray left after the band’s May 23rd gig in Minnesota and flew back to the UK to record what was in the end a minimal change. The brand name “Coca-Cola” was replaced with the generic product descriptor “cherry cola”. Ray caught another flight back to the States re-joining the tour for their next gig in Chicago

With a one-day gap in their schedule, Ray left after the band’s May 23rd gig in Minnesota and flew back to the UK to record what was in the end a minimal change. The brand name “Coca-Cola” was replaced with the generic product descriptor “cherry cola”. Ray caught another flight back to the States re-joining the tour for their next gig in Chicago