Lessons from past crises – looking for opportunities, I’ll drink to that

This week’s story is about a family owned business that is now the leading provider of Californian wines – E & J Gallo. The story is about how the brand followed a simple but effective strategy at the end of the Great Depression (and the end of Prohibition) and then drove further growth after WWII.

While Californian wines really rose to international prominence in the 1970s and 80s, the history of wine in the region goes back much further. Californian wines had been successful in international competitions as far back as the early 1900s. The double whammy of Prohibition, which was introduced in January 1920, coupled with the Great Depression (which also started in 1929), meant the once thriving industry went into a steep, almost terminal decline. Vines were uprooted across thousands of acres and cash crops such as apples and walnuts were planted in their stead.

When Prohibition was repealed on December 5, 1933, only 160 of California’s original 700 wineries were intact, and taxation and legislation had decimated domestic wine consumption.

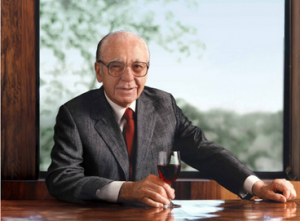

It is at this point that Ernest and Julio Gallo, then aged 24 and 23 years enter our story. Both their parents had recently died, and they needed a plan. They decided to enter the wine business.

They applied for and obtained a winery license. They bought winemaking equipment on credit and leased a small Modesto warehouse for $60 a month. Some sources say that despite having worked in their father’s small vineyard when younger, they got their technical education from two pre-Prohibition wine pamphlets from the Modesto Public Library.

Perhaps even more important was that the brothers recognized that while the Great Depression was ending, money was still tight for most people. They agreed on a marketing strategy that not only reflected this but aimed to take advantage of it. They decided that they would made acceptable wine and sell it at a low price. Their aim was to build volume and gain share.

They then visited local growers, offering them a share of the profits in return for the use of their grapes.

In December 1933, Ernest had made his first sale of 6,000 gallons of wine to Pacific Wine Company, a Chicago distributor. Profit in the first year was $34,000, a sum that was immediately plowed back into the business.

The business grew, but it wasn’t until WWII that Ernest identified an opportunity to drive the business further faster. It was an insight that would make him renowned throughout the industry.

At the time wine was relegated to a position behind beer and hard liquor. It wasn’t the focus and priority for the people in the liquor salesforces.

At a time of uncertainty, Ernst followed his intuition and introduced the novel concept of salespeople who exclusively sold wine. He recruited a team of zealous salespeople to push Gallo products and get them high visibility on the liquor store shelves. It would prove to be a highly successful idea which was soon widely imitated by the other wine makers.

Gallo had always followed a strategy of expanding into new markets only when existing markets were ‘conquered’. The new salesforce accelerated the growth and the brand was soon available nationwide. Nowadays Gallo wine and its numerous brands are available all around the world. Its portfolio runs from more economical brands to super-premium.

What are the implications, if any, for brands now?

Today our economy has fallen in recession, a depression that many analysts are saying could be deeper than the Great Depression. It seems highly likely that value-for-money, economic offerings will do well. (The earlier lesson of the original Mini is another example of tailoring your offer down). What can you do in this sector of the market by broadening your portfolio and changing the focus of your marketing efforts?

The second implication is to try and use the time now to look for opportunities, to try and take a fresh look at your market and address some of the issues and barriers to growth – and if and when you do find new ideas, I’ll raise a glass of Gallo wine to you.