Why researchers tricked a woman into cleaning her floor

Have you ever really thought about what happens when you mop a floor?

You take your mop and bucket, fill the bucket with water and add your cleaning liquid. Then you plunge the mop into the soapy water and – having wrung it out – start to mop your dirty floor. With luck, you can see the dirt ‘disappearing’ with every wipe. After a few wipes you plunge your mop back into the bucket and wring it out. Now you’re ready to start mopping again, and on its goes till the floor is ‘visibly’ clean.

Job done…or is it?

Let’s think about this whole process a bit more closely.

After wiping the floor for the first time you plunge a dirty mop into the soapy water to ‘clean it’– the dirt on it comes off, but that dirt doesn’t disappear. In fact it contaminates the clean soapy water making it dirty soapy water.

The next time the mop is plunged into the bucket, even if wrung out, it will come out as a dirty, damp mop and you are going to use it to clean your floor.

You’re not removing the dirt, you’re just moving it around.

It was this thinking that led the Director of Corporate New Ventures at Procter & Gamble to say “There has got to be a better way to clean a floor. Current mops are the cleaning equivalent of the horse drawn carriage – where’s the car?”

P&G decided they needed to really understand how people cleaned their kitchen floors. Ethnographic researchers were sent into people’s homes to watch them clean, dust, wipe and mop.

At first the results just didn’t seem quite right; it all seemed too easy. It was then that the researchers realised that many of the people they were coming to watch had already cleaned their house because someone – the researcher – was coming to visit.

The researchers decided they would have to be sneakier. They started arriving with dirty shoes and surreptitiously spilling dirt or dust.

One day, one of the research teams spilled some coffee grounds while visiting an elderly respondent.

However rather than breaking out a mop, the grandmother swept up the grounds with a broom and then proceeded to use a damp paper towel to clean up the rest of the fine dust.

In that moment inspiration struck and the Swiffer was born. An electrostatic cleaning system designed to facilitate both sweeping and mopping with a single mess-free device. It would be a variation on “the razor and blade system” whereby the heads would be regularly replaced.

In the year after its July 1999 introduction, more than 11.1 million Swiffer starter kits were sold.

The Swiffer remains one of Procter & Gamble’s most popular consumer products with annual sales of $500 million.

It’s a great innovation born of identifying a problem others hadn’t seen before, and persevering and adapting the research approach to get to the right results.

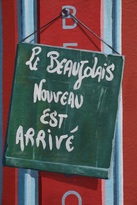

Beaujolais had always made a “vin de l’année” to celebrate the end of the harvest, which was drunk in the local bars, cafes, and bistros of Beaujolais and Lyons. Each autumn the new Beaujolais would arrive. It was a wine made quickly and designed to be consumed immediately – taking only weeks from grape to glass. The better Beaujolais were allowed to take a much more leisurely course.

Beaujolais had always made a “vin de l’année” to celebrate the end of the harvest, which was drunk in the local bars, cafes, and bistros of Beaujolais and Lyons. Each autumn the new Beaujolais would arrive. It was a wine made quickly and designed to be consumed immediately – taking only weeks from grape to glass. The better Beaujolais were allowed to take a much more leisurely course.