Brotherly Love?

As an AFOL (Adult fan of Lego) a number of colleagues, friends and clients have sent me information about the Addas Lego partnership and the new trainers. I may or may not succumb – though possibly not as I think there isn’t enough building, construction/deconstruction element. However thinking about Adidas reminded me of the story of its origins of Adidas… and how it is linked to the launch of Puma whose trainers are my trainers of choice.

I thought it would be timely to share it

Brotherly love?

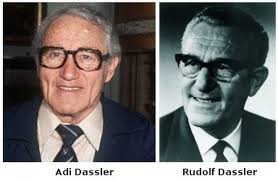

Christoph Dassler worked in a shoe factory. He had two sons, Adolf and Rudolf.

Returning from World War I, the brothers went different ways. Adolf – known as Adi – kept the family’s interest in shoes going and began producing his own sports shoes in his mother’s wash kitchens. Meanwhile Rudolf, or ‘Rudi’, took up a management position at a porcelain factory, later joining a leather wholesale business.

Rudi returned to their hometown of Herzogenaurach in July 1924 and joined his younger brother’s business. It was renamed the Gebrüder Dassler Schuhfabrik (Dassler Brothers Shoe Factory) and began to prosper.

With the 1936 Summer Olympics in Germany pending, Adi spotted an opportunity. He travelled to the Olympic village with a suitcase full of their shoe spikes, and there persuaded U.S. sprinter Jesse Owens to use them. It was the first commercial sponsorship of an African American.

When Owens won four gold medals, the reputation of Dassler shoes rose. Letters from around the world landed on the brothers’ desks, as sportsmen and coaches of other national teams became interested in their shoes.

Business boomed, and by the late 1930s the Dasslers were selling some 200,000 pairs of shoes a year.

Like most brothers, Adi and Rudi had many arguments, but it was during the course of the Second World War that they were to fall out. Though both brothers joined the Nazi party, relationships were strained, and reached breaking point during a bomb attack in 1943.

Rudi and his family were sitting in a bomb shelter when Adi and his wife arrived. Rudi heard his brother say: “The dirty bastards are back again”.

Thinking that Adi was referring to him, and not to the Allied war planes, Rudi was furious.

It didn’t help that their wives didn’t like it other.

The situation continued to worsen but when in the aftermath of the war Rudi was picked up by American soldiers and accused of being a member of the Waffen SS, it reached boiling pint. Rudi was convinced that his brother had turned him in.

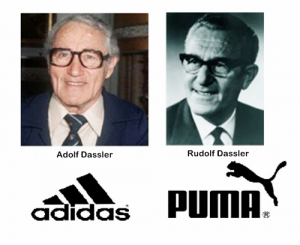

The brothers split in 1947.

Rudi formed a new firm that he initially called Ruda – a worger (word merger) of Rudolf Dassler – later rebranded Puma, while Adi formed Adidas AG. While it is sometimes claimed that the name is an acronym for ‘All Day I Dream About Sport’, the name is actually another worger of ‘Adi’ and ‘Das(sler)’.

The rivalry between the two businesses was fierce and bitter. Herzogenaurach was equally split and acquired a new nickname: “the town of bent necks”, referring to the townspeople’s habit of forever looking down to check which brand of shoes strangers were wearing. However, both brands prospered.

And the moral is, competition can often be good for both parties. How can you use your competition to your advantage?