The Wasp

“It looks like a wasp!”

Not quite the endorsement that Corradino D’Ascanio was expecting when he presented the fruits of his hard work to his patron.

Yet within months the Italian language possessed a new verb based on the brand.

To date over 16 million of them have been sold around the world and they are produced in 13 countries.

They have become a screen icon starring alongside Audrey Hepburn in Roman holiday, Anita Edberg in La Dolce Vita, Angie Dickinson in Jessica and Gwen Stefani in her 2007 video for Now That You Got It.

If you still haven’t got the brand, they also appeared in Quadrophenia where ever Mod who could afford one, was riding one.

The brand is of course Vespa.

Following the end of the war, industrialist Enrico Piaggio needed to find a new direction for his company, which had been making planes for the Italian air force. He recognised that Italy had an urgent need for a modern and affordable mode of transport. He therefore tasked one of his aeronautical designers, Corradino D’Ascanio, with designing a motorcycle suitable for getting around the bomb-damaged Italian cities.

However, D’Ascanio wasn’t keen on motorcycles. He thought they were too cumbersome, too difficult to repair and generally dirty.

Instead, he took inspiration from having seen US military aircraft drop tiny, olive green Cushman Airbornes to their troops in the war-torn cities of Milan and Turin. The Cushman Airborne was a basic, skeletal, steel motor scooter that allowed troops to nip about the rough terrain.

Adapting his aeronautical expertise to the task in hand, he designed a simple but practical scooter. He moved the gear lever onto the handlebar for easier access. He designed the body to absorb stress in the same way as an aircraft would. The seat position was created to give both safety and comfort while the workings were hidden behind panels to keep the rider’s clothes in pristine condition and the step-through frame meant it was an ideal machine for skirt-wearing women to ride.

In fact, the first Vespas built actually used components from Piaggio’s aircraft; the nose wheel suspension for the front wheel of the scooter.

It was however its narrow-waisted design and buzzing sound that caused Enrico Piaggio to exclaim “Sembra una vespa!” (“It look like a wasp!”). A stroke of fortune as the reaction gave the new scooter its brand name.

In April 1946 the Vespa debuted at a golf club in Rome and was an immediate success. It wasn’t long before “vespare” (to go somewhere on a Vespa) was being heard on the streets along with the wasp-like buzzing of their engines.

And the moral is that skills in one sector can be successfully transferred into other sectors. Where could you take your brand?

New book launch & the story that gave the book its title

Many thanks to everyone who came along to the new book launch at The Museum of Brands on 6th April.

I introduced the book and told a couple of the stories in it, and then got a couple of my colleagues to retell their favourite story in their own style

If you couldn’t make it but want a flavour of it, here is a short clip of me telling the story that gave the book its title

Its available on amazon if you are interested

Will the real Quakers please stand up.

Quakers are members of a group with Christian roots that began in England in the 1650s. The formal title of the movement is the Society of Friends or the Religious Society of Friends

There are two stories as to how the movement got its name. The first says that the founder, George Fox, once told a magistrate to tremble (quake) at the name of God and the name ‘Quakers’ stuck. The alternative theory is that the name derives from the physical shaking that sometimes went with Quaker religious experiences. There is less controversy about where the name ‘Friends’ comes from. General agreement is that is relates to Jesus’ remark “You are my friends if you do what I command you” (John 15:14).

There are two brands that are linked with Quakers, one is Cadbury and the other is Quaker Oats. Despite the names, it is the former that is really connected to the Quakers.

The Cadburys were a true Quaker family who had moved from Exeter to run a draper’s shop in Birmingham by the start of the 19th Century. At the time Quakers were barred from the universities so could not pursue professions such as medicine and the law. Nor, as pacifists, could they could consider naval or military careers, which is perhaps why they turned their attention to trade.

Quakers are also teetotal and as such keen to promote alternatives to alcohol, so it was perhaps not surprising that in 1824, that John Cadbury opened a tea and coffee shop next door to his father’s drapery in Bull Street.

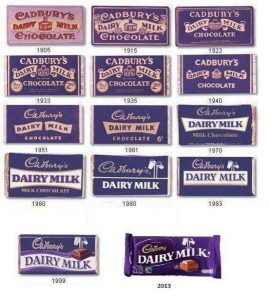

He was soon to branch out into cocoa, often grinding the beans himself, and by 1831, the shop was devoted entirely to drinking chocolate. By the 1850s, Cadbury had been given a Royal Warrant from Queen Victoria and, in 1860; John’s sons George and Richard imported a Dutch chocolate press and made something akin to what we would recognise as a bar of chocolate.

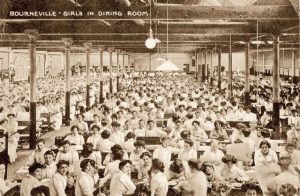

It was great success result and the brothers were soon very wealthy. They didn’t however spend all their new gained riches on themselves, instead appalled by deplorable living standards in Birmingham, George and Richard set out on a vision to create a ‘ factory in the country’.

It was great success result and the brothers were soon very wealthy. They didn’t however spend all their new gained riches on themselves, instead appalled by deplorable living standards in Birmingham, George and Richard set out on a vision to create a ‘ factory in the country’.

They bought a farm on the banks of the River Bourn and named it ‘Bournville’. They built not only a huge factory but also hundreds of bright airy homes with gardens and fruit trees for their workers. The village included open spaces, trees and public baths but of course no pubs. When Richard died in 1899, George placed the entire 1,000-acre community into a trust. Today, many of its 25,000 residents still work for Cadbury and rent their homes from the Bournville Village Trust.

They bought a farm on the banks of the River Bourn and named it ‘Bournville’. They built not only a huge factory but also hundreds of bright airy homes with gardens and fruit trees for their workers. The village included open spaces, trees and public baths but of course no pubs. When Richard died in 1899, George placed the entire 1,000-acre community into a trust. Today, many of its 25,000 residents still work for Cadbury and rent their homes from the Bournville Village Trust.

There are still no pubs in Bournville – and it contains the only alcohol-free branch of Tesco in Britain.

All of which help re-inforce the image of Quakers as upright, honest and decent people, exactly the qualities for which Henry Seymour and William Heston chose the name Quaker Oats

Neither Seymour nor Heston were Quakers, but they selected the Quaker name as a symbol of good quality and honest value.

Today, General Mills who own the brand say, “The ‘Quaker Man’ does not represent an actual person. His image is that of a man dressed in Quaker garb, chosen because the Quaker faith projected the values of honesty, integrity, purity and strength.”

Today, General Mills who own the brand say, “The ‘Quaker Man’ does not represent an actual person. His image is that of a man dressed in Quaker garb, chosen because the Quaker faith projected the values of honesty, integrity, purity and strength.”

Early Quaker Oats advertising dating back to 1909 seems to contradict this and in fact identifies the “Quaker man” as William Penn, the 17th-century philosopher and early Quaker. The ad refers to him as “standard bearer of the Quakers and of Quaker Oats.”

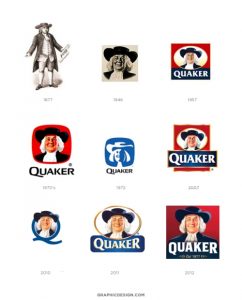

Resembling classic woodcuts of Penn’s likeness, the Quaker Man figure was depicted full-length, sometimes holding a scroll with the word “Pure” written across it. This image was America’s first registered trademark for a breakfast cereal. The registration took place on September 4th, 1877.

Since then the icon has gone through a number of redesigns and refreshes – to add colour, to take it away again, to slim the figure.

However, one of the most famous provides a link to another famous brand. In 1957 Haddon Sundblom produced a colour head-and-shoulders portrait. Sundblom’s other famous brand characters include Coca-Cola’s original Santa and his Quaker Man is said to actually be a portrait of fellow Coca-Cola artist, Harold W. McCauley.

Generally, the Quakers themselves have not said much about this use (or misuse) of their name but have occasionally expressed their anger. One instance was in 1990, when some Quakers started a letter-writing campaign after a Quaker Oats advertisement depicted Popeye as a “Quaker Man” who used violence against aliens, sharks, and Bluto.

Footnote: British confectionary and Quaker beliefs seem to have gone hand-in-hand as Fry’s, Rowntree’s and Terry’s were all founded by Quaker families too.

Once upon a brand

I want to tell you a story ….well actually I don’t, but I wanted to get your attention.

Brand storytelling is undoubtedly ‘hot’ in marketing at the moment, and it seems everyone wants to jump on the bandwagon, and everything is a story.

All of which just goes to show that storytelling as with so many terms in marketing has become over-used and is in danger of being under-valued. This is a shame as storytelling in its various forms has many different uses and has so much to offer.

Having personally already jumped firmly onto the bandwagon with my new book of brand stories about to be published – “How Coca-Cola took over the world”, I thought it might be useful to stop and consider what I thought to be the different categories of stories and their different roles.

While there are probably more categories, I would suggest that there are four variations that are most frequently used. To help differentiate them as with all good segmentations I have given them each different names.

The brand narrative

This is a means of presenting the organisation/brand as a character and its role as a story. Virgin, for example, has positioned itself as the “white knight” riding to save the damsel (us, consumers) in distress, rescuing us from the clutches of big bad corporations. This fits with well with another ‘hot’ topic in marketing at the moment – brand purpose – because a good brand narrative sets out who you are, what you do, why you do it (your purpose) and the benefits you deliver by doing it well.

Brand tales

This is when brands build emotional engagement by telling the little (true) tales about themselves – how the brand started, the origin of its name, etc. These can be used to build emotional engagement both internally and externally. It has increasingly been used in advertising and on packaging.

The “story-point”

When did a PowerPoint slide last make you cry? (Apart from …with boredom). Writing a presentation as a story is one way to try to avoid “death by PowerPoint”. Using a clear narrative arc, personalising the issues and using other storytelling techniques like ‘the power of three” allows speakers to communicate points in a more engaging and memorable way. People remember stories better than bar graphs.

Brand fables

Brand fables

The use of stories about brands as a training tool, to provide inspiration and/or instruction for the marketing team or broader organisation. They can be used to show how employees should act, as a means of helping your organisation consider how it might perform better, or to encourage people to think in different ways. This is of course where my book sits as the each tale ends with a moral and a challenge to think how you could apply it.

So while this hasn’t been a story, there is perhaps a moral and a challenge –

Storytelling comes in many forms and each has its own role. How and when can you use storytelling effectively?

Originally posted at https://www.marketingsociety.com/the-gym/once-upon-brand#Tw3PCWgVWMW5toyU.99