A very Russian American brand icon

One of the most famous American brand icons of all time wouldn’t exist today if it wasn’t for the Russians, or more particularly one specific Russian – Jacob Youphes.

Even those amongst you who might have correctly guessed at the brand being Levi’s 501s and who know their jeans history would be forgiven for still being confused; didn’t Levi Strauss create Levi 501s?

Well the correct answer is yes …and no.

501s were and are produced by Levi Strauss, but the distinctive and differentiating features of the brass rivets and the double orange threaded stitching were innovations of Jacob Davis.

Davis doesn’t sound very Russian, but then again he wasn’t born Jacob Davis. Jacob was born in 1831 in the city of Riga, then part of the Russian Empire, now the capital of Latvia. He was christened Jacob Youphes and was trained and worked as a tailor.

In 1854 he emigrated to the United States where, shortly after arriving in New York, he decided to change his name and became Jacob Davis.

After a number of years travelling and working in various states he finally settled in Reno where he opened a tailor’s shop in 1869.

Much of his trade was in practical hard-wearing items such as tents, horse blankets and wagon covers for the railway workers on the Central Pacific Railroad. The fabrics he worked with were a heavy-duty cotton “duck” cloth and a heavy-duty cotton “denim” cloth.

He bought this latter fabric from a certain Levi Strauss & Co., a dry goods company in San Francisco.

In December 1870 Davis was asked by a customer to make a pair of strong working pants for her husband who was a woodcutter.

Thinking how to create suitably robust pants for working he decided to use the duck cloth and then he had an idea to apply an approach he was already following on his tents and wagon covers. He decided to reinforce the potentially weaker points with the copper rivets, putting them in the seams and pockets in his new trousers.

His customer and her husband were delighted and told their friends and colleagues. Word spread throughout the labourers along the railroad. Davis was soon making more and more of his working pants in both duck cotton and, as early as 1871, in denim cotton too.

Realising the potential value in his reinforced jeans concept, but recognising he would need help and capital if his new pants were going to be a success, he approached Levi Strauss in 1872, asking for his financial backing in the filing of a patent application.

Strauss too could see the potential, and on May 20, 1873, US Patent No. 139,121 for “Improvements in fastening pocket openings” was issued in the name of Jacob W. Davis and Levi Strauss and Company.

Strauss too could see the potential, and on May 20, 1873, US Patent No. 139,121 for “Improvements in fastening pocket openings” was issued in the name of Jacob W. Davis and Levi Strauss and Company.

That same year, Davis started sewing a double orange threaded stitched design onto the back pocket of the jeans to distinguish them from those made by any of his competitors. This feature would be registered too; U.S. Trade Mark No.1,339,254.

Strauss set up a new and sizeable tailor’s shop in San Francisco for the production of Davis’s working pants and asked Jacob and his family to come to the city and run this shop.

As demand continued to grow, the shop was superseded by a manufacturing plant that Davis was then asked to manage. Davis continued to work there for the remainder of his life, overseeing production of the work pants as well as other lines including work shirts and overalls.

The brand however resided with Strauss and over time Jacob’s contribution has become less well-known.

Nowadays the Russian’s contribution is known only by fashion and brand historians … and you.

The next big change happened when Lipton went on “vacation” to Australia. In fact, he never planned on going to Australia, the story was a cover for a trip to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). There a recent blight had ruined the English coffee planters, and the survivors were now planting tea. With land prices low, Lipton had spotted another opportunity and bought five of the bankrupt plantations. This and his subsequent acquisition of about a further dozen sites allowed him to unveil a new slogan, “Direct from the Tea Gardens to the Teapot.”

The next big change happened when Lipton went on “vacation” to Australia. In fact, he never planned on going to Australia, the story was a cover for a trip to Ceylon (Sri Lanka). There a recent blight had ruined the English coffee planters, and the survivors were now planting tea. With land prices low, Lipton had spotted another opportunity and bought five of the bankrupt plantations. This and his subsequent acquisition of about a further dozen sites allowed him to unveil a new slogan, “Direct from the Tea Gardens to the Teapot.”

As the existing factory in Dehiwala was restricted in its capacity, the company opened a new biscuit factory at

As the existing factory in Dehiwala was restricted in its capacity, the company opened a new biscuit factory at  Mineka is now the president emeritus focused on quality improvements and innovation. He has set up other companies in confectionery, canning and hospitality. He has served as the chairman of the Southern Regional Economic Development Commission.

Mineka is now the president emeritus focused on quality improvements and innovation. He has set up other companies in confectionery, canning and hospitality. He has served as the chairman of the Southern Regional Economic Development Commission.

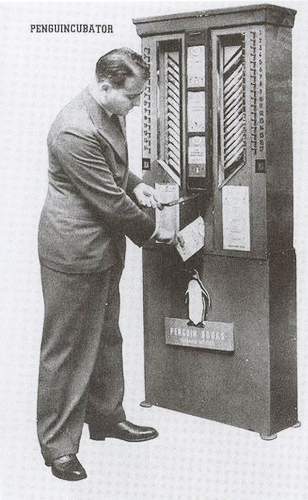

It was then that Mrs Prescott spotted the Agatha Christie Poirot Book “The Peculiar Affair at Styles” lying amongst the assorted titles spread around her husband’s meeting table. She enquired whether the firm was considering selling the softcover books, and announced that she would buy several a week if the price were sixpence or less.

It was then that Mrs Prescott spotted the Agatha Christie Poirot Book “The Peculiar Affair at Styles” lying amongst the assorted titles spread around her husband’s meeting table. She enquired whether the firm was considering selling the softcover books, and announced that she would buy several a week if the price were sixpence or less.