A tagline is forever

A few weeks ago I told the story of Tiffany’s blue box, so it only seems sensible to tell the story of how so many of the rings inside those boxes came to include a diamond

A tagline is forever

In the 1930s, presenting a woman with a diamond engagement ring when proposing was not the social norm it is nowadays and the Depression had made matters even worse for De Beers, the brand which controlled 60% of rough diamond output.

De Beers decided to embark on what they now describe as a “substantial” campaign, linking diamonds with engagement. They hired Philadelphia based dvertising agency N.W. Ayer in 1938 to try and make Americans fall in love with diamond engagement rings.

At the time only 10% of engagement rings contained diamonds and they were seen as an extravagance for the wealthy. Sales, already declining for more than two decades, had plummeted during the Great Depression.

The challenge Ayer faced wasn’t easy and as internal Ayer documents later observed the campaign required “the conception of a new form of advertising, which has been widely imitated ever since. There was no direct sale to be made. There was no brand name to be impressed on the public mind. There was simply an idea — the eternal emotional value surrounding the diamond.”

The new campaign was to weave together two strands

The first strand was to suggest a diamond’s worth and manage expectations as to what to a man should pay for a diamond by proposing, at least in the 1930s and 40s, that it should be equivalent to a single month’s salary (A figure that would obviously go up with inflation but which has also been increased to two months in the 1970s and 80s and more recently has become three months’ salary)

The second strand happened in 1947 when at a routine morning meeting, Frances Gerety, a young copywriter, suggested a new tagline. Her colleagues weren’t particularly impressed. The all-male group felt it didn’t mean anything and that it wasn’t even grammatically correct.

The second strand happened in 1947 when at a routine morning meeting, Frances Gerety, a young copywriter, suggested a new tagline. Her colleagues weren’t particularly impressed. The all-male group felt it didn’t mean anything and that it wasn’t even grammatically correct.

Gerety who had been working on the De Beers account since 1942, had often explored ideas of eternity and sentiment. Her previous ads which had appeared in publications like Vogue, Life, Collier’s, Harper’s Bazaar and the Saturday Evening Post had suggested things like “May your happiness last as long as your diamond.” or “Wear your diamonds as the night wears its stars, ever and always . . . for their beauty is as timeless.”

Her new line “A Diamond is Forever” was the summation of her thinking and was the turning point in the campaign.

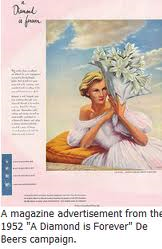

Despite those early misgivings “A Diamond Is Forever” first appeared in a 1948 ad and has appeared in every De Beers engagement advertisement since then.

By 1951, Ayer was seeing success and informed De Beers that “jewellers now tell us ‘a girl is not engaged unless she has a diamond engagement ring.’ ”

In 1956, Ian Fleming’s 1956 novel, “Diamonds Are Forever,” the fourth in the James Bond series was published and subsequently turned into a film with a memorable theme tune of the same name sung by Shirley Bassey.

In 1999, Advertising Age proclaimed it the slogan of the century: “Before the DeBeers mining syndicate informed us ‘A Diamond Is Forever,’ associating itself with eternal romance, the diamond solitaire as the standard token of betrothal did not exist,” the magazine explained. “Now, thanks to the simple audacity of the advertising proposition, the diamond engagement ring is de rigueur virtually worldwide, and the diamond by far the precious gemstone of choice.”

By the end of the 20th Century, 80% of engagement rings contained diamonds because, as all husbands know, she’s worth it.

After the death of his father in 1928, Spedan assuming control of the Oxford Street store too and in 1929 officially formed the John Lewis Partnership, and began the distribution of profits among its employees

After the death of his father in 1928, Spedan assuming control of the Oxford Street store too and in 1929 officially formed the John Lewis Partnership, and began the distribution of profits among its employees

The original Norman archer logo that went with the new name was designed by artist Barney Bubbles. Barney Bubbles (born Colin Fulcher) was a radical English artist whose work encompassed graphic design and music video direction. He is in fact best known for his later association with the British independent music scene of the 1970s and 1980s and artists such as Ian Dury & the Blockheads, Elvis Costello and The Damned. His record sleeves for them are amongst his most recognisable output, though in reality possibly more people saw and would recognise his work for Strongbow and Bulmers.

The original Norman archer logo that went with the new name was designed by artist Barney Bubbles. Barney Bubbles (born Colin Fulcher) was a radical English artist whose work encompassed graphic design and music video direction. He is in fact best known for his later association with the British independent music scene of the 1970s and 1980s and artists such as Ian Dury & the Blockheads, Elvis Costello and The Damned. His record sleeves for them are amongst his most recognisable output, though in reality possibly more people saw and would recognise his work for Strongbow and Bulmers.