Refreshing the advertising – hit or myth

The British love beer

The British love their beer advertising

The British advertising industry loves an advertising myth

Heineken’s famous “Refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach” campaign scores on all three counts.

The myth runs that one of the best beer advertising campaigns was created by a creative team who, without an idea in their heads fled the country with a one-word brief and the threat of being firing if they didn’t come back with a campaign. The second half of the myth is that the campaign was nearly killed by initial negative research but only saved by a client who chose to ignore the findings.

The myth

It was the early 1970s, a period when bitter dominated the UK beer market but lager was starting to grow rapidly, and copywriter, Terry Lovelock and art director, Vernon Howe from the agency CDP were given the brief to creating a TV campaign for Dutch lager Heineken. Their brief was just one word – Refreshment.

They were struggling and hadn’t come up with anything any good. They decided to try new surroundings and decided to head for Marrakesh. On their way out, they met Frank Lowe the head of the agency who told them to make sure they came back with a campaign or not to come back at all.

The story continues, according to the book ‘Inside CDP’; “Lovelock was now desperate. He walked around Morocco with pen and paper in hand searching for the idea. Lovelock said that, “At the back of my mind, there was a thought that if booze causes some strange metamorphoses, it must be possible to explain its effects on the body in a fun way”. One evening Terry went to bed around midnight, notepad nearby. At 3am, he woke from a dreamless sleep and sat upright. He grabbed the notepad and wrote two lines. ‘Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach’ and ‘Heineken is now refreshing all parts’. The following morning he wrote two scripts.”

The story continues, according to the book ‘Inside CDP’; “Lovelock was now desperate. He walked around Morocco with pen and paper in hand searching for the idea. Lovelock said that, “At the back of my mind, there was a thought that if booze causes some strange metamorphoses, it must be possible to explain its effects on the body in a fun way”. One evening Terry went to bed around midnight, notepad nearby. At 3am, he woke from a dreamless sleep and sat upright. He grabbed the notepad and wrote two lines. ‘Heineken refreshes the parts other beers cannot reach’ and ‘Heineken is now refreshing all parts’. The following morning he wrote two scripts.”

Frank Lowe loved the idea and presented it to the key client, Anthony Simonds-Gooding while the pair were on a flight to St Petersburg. He had written it on a sick bag. Simmonds-Gooding loved the idea too despite the presentation material.

Despite this, according to the myth, the ads however nearly didn’t run. The research was extremely damning.

Reviewing the events in 2012 Campaign, the UK’s leading advertising magazine picked up the tale. ‘In these days of campaigns being researched to within an inch of their lives, it’s debatable whether “refreshes the parts” would have made the cut, let alone run for two decades. The story of how the ads made it through raises a question whose relevance has not diminished over time: how much should research results dictate whether a creative idea lives or dies?’

Had Anthony Simonds-Gooding, then the Whitbread marketing director, chosen not to follow his instincts after seeing poor feedback from the first three ‘refreshes the parts’ TV spots, the campaign would have been stillborn. But Simonds-Gooding pressed on.

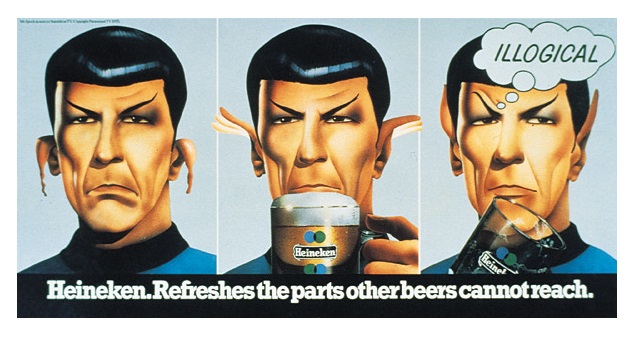

The ads however did indeed run and the campaign was to stretch over the next two decades, including famous ads like Policeman, Spock’s ears and Majorca.

Separating the myth from history

Like many myths there is a great deal of truth in this tale, but some parts have perhaps been distorted or exaggerated for effect over the years, so following a little research of my own I thought I would point out a few points of contention.

It is true that Terry Lovelock and Vernon Howe of CDP had indeed been given the brief to create a new campaign for Heineken. However while the key word they were asked to focus on was “Refreshment” – this was part of an overall creative brief which contained background, target audience and desired tone of voice. However, like many briefs of the time it was reduced to a single thought or word as shorthand summary of the requirements. They idea that they were only given a single word adds to the drama but not the truth.

The notion that they just decided to try a new location and just head off to Marrakesh fits with ideas of the glamorous and free-spending nature of the advertising world in the 1970s. However, the real reason they left for Marrakesh was for a photographic shoot for Ford. Without the need for the shoot, the new locations would probably have been the local pub.

It seems plausible that Frank Lowe would have said to them to come back with something or don’t come back at all – whether he actually meant it was another thing.

Vernon Howe would have been focused on the shoot, so it’s not too surprising that Terry Lovelock “walked around Morocco” as recalled in the passage form ‘Inside CDP’.

The next area of controversy is the research and those negative findings.

The next area of controversy is the research and those negative findings.

As we have seen, the Heineken campaign has long been held up as an example of the tension between creativity and research and used to highlight the danger of research.

The counter argument which has more recently been presented by Kevin Wardle and others is that the research wasn’t the ‘blunt instrument’ which tried to bludgeon this great advertising to death. Rather it was then and is now a tool that “can and does contribute to great advertising.”

Perhaps one of the most interesting points to come to light is that the research everyone refers to took place in April 1974. What’s so interesting about that is that the campaign first appeared in March 1974 – so the research didn’t stop its running.

What that research said, once it had been conducted, contained both negative and positive elements.

There were negative comments about the specific executions – ‘what’s beer got to do with ears?’ (Piano Tuner) and ‘not the sort of thing you’d like to see when you’re eating your tea’ (Policemen) and some respondents failed to get the connection between the beer’s restorative powers and refreshment – ‘beer’s supposed to refresh you, they say it’s a medicine’.

There was also a respondent’s snap judgement about the strapline, which the researcher passed on to the clients and the agency – ‘On its own it doesn’t stick. No rhythm about it’

However more positively the report also said that the advertising was on strategy, and endorsed the need to focus on refreshment as a point of difference and raison d’etre for lager and for this brand.

So like most good research it provided information and interpretation, which the client could then make a judgement call on and that’s exactly what Anthony Simonds-Gooding did.

A footnote

When Australian lagers arrived in the UK in the 80s, Heineken decided it needed to reinforce its European credentials and hired comedian Victor Borge for the voiceovers. This was an interesting choice, since Heineken is Dutch and Borge was Danish, so there is probably another tale to be told.