Have you heard the one about the Peddler, the Jeweller and the Attorney?

Don’t worry it is a clean story.

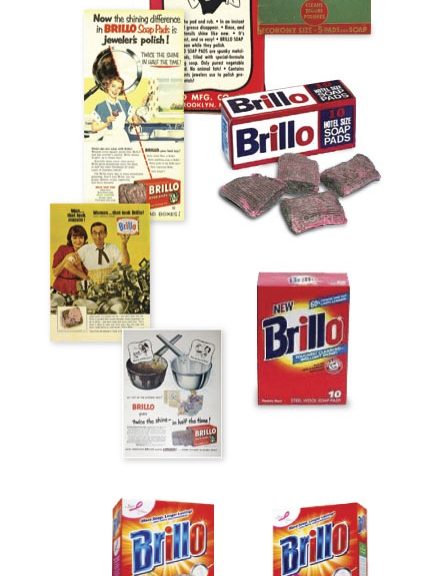

In fact, it’s a story about one of the world’s most famous cleaning brands. A brand that was turned into an icon by Andy Warhol.

The story starts in the early 1900s, when aluminium pots and pans were starting to replace the traditional heavy cast iron cookware in homes throughout America…but, there was a problem which was slowing the transition down. The coal-fired stoves of the day quickly blackened the aluminium pots making them both unattractive and difficult to clean. The new gas stoves of the time weren’t much better depositing soot onto the pans.

A New York door- to-door peddler named Brady found that this problem was limiting his sales of pans. He decided he needed to do something about it, and so started to experiment with different soaps and rolls of steel wool. He wasn’t satisfied with the results he got. The pans were clean but didn’t regain their shine.

Brady decided to consult his brother-in-law, a Mr. Ludwig, who was a costume jeweller and had different ways and products that he used to clean the different metals, glass and jewels of his particular trade. Drawing on this knowledge, Ludwig suggested what seemed obvious to him. Why not combine soap with jeweller’s rouge. Now jeweller’s rouge is finely ground ferric oxide and is regularly used as a polish for metals and optical glass, as it helps bring out the maximum lustre and can help create a mirror-like finish.

The resulting combination of steel wool and a bar of a mix of soap and jeweller’s rouge worked cleaning and restoring the desired shine.

Brady added the new product to his line of goods. Almost immediately, he found that it was out-selling his pans.

Brady and Ludwig wanted to move into commercial production and realized that they needed to patent their idea. They sought advice from an attorney named Milton Loeb. However, their funds were limited and so offered Loeb an interest in their fledgling business instead of his fee. Loeb obviously saw the potential and not only accepted the stake, he joined the company, going onto become treasurer and president.

It is Loeb who suggesting the “Brillo” name, under which the soap bar was duly patented and registered as a trademark in 1913. The partnership formed between the peddler, the jeweller and the attorney became known as the Brillo Manufacturing Company, with its headquarters and production operations in Brooklyn.

By 1917, the Brillo Manufacturing Company was making steel wool pads and packaging them, five pads to a box, with a cake of soap included. In 1921, the Brillo Manufacturing Company moved to bigger premises in London, Ohio.

In the early 1930s the next and perhaps most dramatic step in the brand’s evolution happened, when the company developed a method to put the soap into the heart of the pads themselves creating something close to what we know today as the classic Brillo pad.

The new soap filled pads were a success and Brillo went on to become one of America’s most recognizable brands, but it was in the 1960s when Andy Warhol’s produced his oversize replicas of the bright, simple and bold packaging that Brillo became a true marketing icon.

(Many thanks to Paul Walton for pointing in the direction of the story which he had previously used in a presentation about triggers for innovation)