Making healthcare better

The tale behind the NHS and how storytelling played a role (along with many other things)

I have long thought that the NHS is an amazing brand and, as someone who is fascinated by the stories behind brands, I’ve been doing a little digging and was fascinated to see how storytelling, a hot marketing topic, played a part in the brand’s birth.

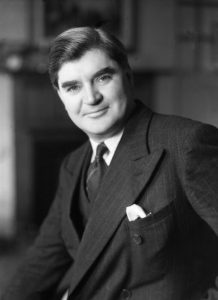

Like so many innovations much of the credit is given to one founding father and the rest of the ‘family’ are forgotten. While Aneurin or ‘Nye’ Bevan does deserve much praise for the birth of the UK’s National Health Service (the NHS) it is worth telling the full story and celebrating some of the other characters along the way.

The story begins nearly 40 years before that momentous day, the 5th July 1948; the day when The National Health Service, was launched by the then Minister of Health in Attlee’s post-war government, Aneurin Bevan, at the Park Hospital in Manchester.

In those days at the turn of the century, if someone found themselves needing a doctor or to use medical facilities, they were generally expected to pay for those treatments themselves. In some cases, local authorities ran hospitals for the local ratepayers especially the less well off, an approach originating with the Poor Law.

The specific ‘germ’ of the idea for the NHS is generally traced back to 1909 and the publication of the Minority Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Law. The committee was headed by the socialist Beatrice Webb. She and her fellow committee members argued that a new system was needed to replace the ideas of the Poor Law as those ideas were now antiquated as they had been around since the times of the workhouses of the Victorian era. The report said that it was narrow-minded and unfair to expect those in poverty to be entirely accountable for themselves and their health. The ideas were however ignored by the then new Liberal government.

However, beyond parliament, the report did prompt others to start advocating changes. These included Dr Benjamin Moore, a Liverpool physician who wrote about the need for “The Dawn of the Health Age”. Moore was probably the first to use the phrase ‘National health service’. He went on to set up State Medical Service Association which held its first meeting in 1912.

The next landmark came in 1929 when the Local Government Act of that year pushed local authorities to run services which provided medical treatment for ‘everyone’. On 1st April 1930, the London County Council took over responsibility for around 140 hospitals, medical schools, and other institutions. Adoption elsewhere was piecemeal.

The next character to join the fray was Dr. A.J Cronin and his contribution was a work of fiction. He wrote a novel “The Citadel” which was published in 1937. It was both controversial and provocative. It strongly criticised the inadequacies and failures of the prevailing healthcare system. The book told the story of a doctor from a small Welsh mining village who climbed the ranks to become a leading doctor in London. Seduced by the thought of easy money from wealthy clients rather than the principles he started out with, the doctor becomes involved with pampered private patients and fashionable surgeons. But when a patient dies because of a surgeon’s ineptitude, the doctor sees the error of his ways returns to his principles.

Cronin said of his book “I have written in The Citadel all I feel about the medical profession, its injustices, its hide-bound unscientific stubbornness, its humbug … The horrors and inequities detailed in the story I have personally witnessed. This is not an attack against individuals, but against a system.”

The novel was made into a 1938 film which features some of the biggest stars of the day including Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell, Ralph Richardson and Rex Harrison. (In later years it inspired a number of re-makes, and a television series)

All the interest helped provoke more discussion and debate about the notion of a national health service and it was increasingly apparent that there was a growing consensus that the current system of health insurance should be extended to include dependents of wage-earners and that voluntary hospitals should be integrated into a broader service.

However, discussions were to a degree put on hold by the outbreak of the Second World War but, with the importance of health, they were picked up again.

By 1941, the Ministry of Health started to draw up a post-war health policy reflecting a vision that services would be available to the entire general public. A year later the Beveridge Report put forward a recommendation for “comprehensive health and rehabilitation services”, a proposal that was supported right across the House of Commons by all parties.

In 1944 the Minister of Health, Henry Willink, put forward a White Paper, which set out the guidelines for the NHS. The principles included how it would be funded from general taxation and not national insurance, that everyone would be entitled to treatment including visitors to the country and that it would be provided free at the point of delivery.

It was endorsed by the cabinet.

In 1945 Clement Attlee was elected Prime Minister and Aneurin Bevan became Health Minister. He was charged with taking the ideas from Willink’s white paper and turning them into a reality.

Making it happen was a mammoth task. It took three years but ultimately brings the story back to 5th July 1948 and the hospital in Manchester.

So while Bevan took, and still takes most of the headlines, he wouldn’t be remembered if it wasn’t for Beatrice Webb, Dr Benjamin Moore, Dr. A.J Cronin, Henry Willink and many others.

MORAL: Storytelling is a powerful tool for persuading people. Can you use storytelling more in your organization?