The Clever Widow

This tale works for me on many levels. I love champagne, I love brand stories and I want to find more brand stories where the lead character is a woman.

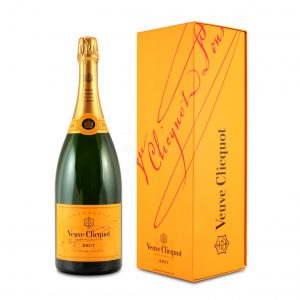

So, when I heard about Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin and her role in creating and building the Veuve Cliquot brand I decided I would have to write my version of the inspiring tale.

Barbe-Nicole Ponsardin was the daughter of an affluent textile industrialist in Reims, France. Next door lived Philippe Clicquot who also ran a successful textile business. They decided that coming together would be better than competing and following a custom prevalent in the 18th century they agreed the best way to seal the alliance was to arrange a marriage between their children.

So, in 1798, when she was 21 years old, Barbe-Nicole married Francois Clicquot, Philippe Clicquot’s only son. Happily, it seemed to work out well.

While the Cliquots’ focus was textiles, they also ran a small wine business. Reims, where the family lived, is in the Champagne region and though sparkling wine had been invented, the Champagne region was at that time more famous for its still white wines. Philippe Cliquot would buy from wine producers and export on; he had no real intention of expanding or moving into production. He used the wine to help fill out the boat loads of textiles he exported.

Francois and Barbe-Nicole had a different plan, and despite Philippe’s reservations they set about learning the wine trade. Despite their passion for the industry, with the Napoleonic wars raging, their champagne business stalled and looked ready to collapse.

In 1805, Francois fell ill and died soon after, amongst rumours that it wasn’t a fever but suicide. Both Barbe-Nicole and her father-in-law, Philippe, were devastated by Francois’ death. Philippe announced that he would exit the wine business.

Barbe-Nicole however had other plans and approached her father-in-law with her ideas. Though he knew she was highly intelligent it is still somewhat surprising that he agreed. He however stipulated that she must first go through a period of apprenticeship. For four years she worked with the well-known winemaker Alexandre Fourneaux trying to make the business profitable.

It wasn’t really working and so Barbe-Nicole went to her father-in-law again, asking for more money, and again he agreed.

This time things aligned better for her. The Napoleonic Wars were ending, and she had plenty of wine in her cellars wine that would become the legendary vintage of 1811, but her success still depended on her taking a huge risk. She knew that there was huge potential in the Russian market for the kind of champagne she had been making – an extremely sweet champagne (it had about twice as much sugar as there is in today’s sweet dessert wines). She wanted to get in early and corner that market.

The problem was that there were still naval blockades. She wanted to get ahead of potential competitors so smuggled much of her best wine to Amsterdam, which would mean a faster route to Russia. When peace was declared the shipment left immediately and her champagne beat that of her competitors by weeks.

Not long afterwards Tsar Alexander I announced that it was the only kind of champagne that he would drink. With this royal endorsement, her wine was a huge success.

Her next problem was that demand was potentially going to outstrip supply. Champagne making, at that time, was a tedious and wasteful business. Champagne is made by adding sugar and live yeast to bottles of white wine, creating a secondary fermentation. As the yeast digests the sugar, the by-products are alcohol and carbon dioxide, which give the wine its bubbles. The problem however is that once the yeast has consumed all the sugar, it dies leaving a winemaker with a sparkling bottle of wine but dead yeast in the bottom of the bottle. The traditional solution was to pour the champagne with the dead yeast from one bottle to another. It was this process that made production so time-consuming and wasteful. It also could ‘damage’ the wine by constantly agitating the bubbles.

To overcome the problem Barbe-Nicole introduced a revolutionary new method, known as riddling. Instead of transferring the wine from bottle to bottle to rid it of its yeast, she kept the wine in the same bottle but consolidated the yeast by gently agitating the wine. The bottles were turned upside down and twisted, causing the yeast to gather in the neck of the bottle.

Not only was this a quicker method, it produced better quality champagnes. Luckily riddling remained a house secret, testimony to the loyalty of her employees. It would be decades before competitors like Jean-Rémy Moët would find out how to replicate her method.

Barbe-Nicole, the clever ‘veuve’ (French for ‘widow’) went on to expand the business and the Veuve Cliquot brand globally before she died in in 1866. She never remarried and some historians believe that was because it would most likely have meant she would have had to relinquish control of her business.

In the later years of her life she wrote the following advice for a grandchild: “The world is in perpetual motion, and we must invent the things of tomorrow. One must go before others, be determined and exacting, and let your intelligence direct your life. Act with audacity.”

The advice rings true for marketers today.

And the moral is if at first you don’t succeed, but you truly believe in what you are doing, try and try again. Is there something you truly believe in that deserves another chance?

Footnote: thanks to Paul Graham, Marketing & Communications Director, UK, Moet Hennessy portfolio who mentioned the story during a webinar hosted by the Marketing Society Scotland