It is more than 100 years since the end of World War One, and it is now hard to imagine the true scale and horror of death and injuries, though recent films like 1917 have gone way in bringing it to life (and death) for a younger generation.

It was another period in history when so many relied on the heroic actions of medical staff: doctors, nurses and ancillaries. Like the current Covid-19 crisis it was also a time of shortages for doctors and nurses. In particular, during the heaviest periods of fighting, soldiers were getting wounded in such large numbers that the medics often ran out of bandages.

Also like now companies and brands stepped up and did their bit. Kimberly-Clark was one of them. It offered the army a new product of theirs, Cellucotton, a highly absorbent fluffy paper wadding product that could be used for filters in gas masks, stuffing for emergency jackets but more importantly for pads and bandages.

By a strange co-incidence the technology for it had been found during a visit to Germany by two Kimberley-Clark executives, Ernst Mahler and company president J.C. Kimberley.

Kimberly-Clark committed to selling Cellucotton to the War Department and Red Cross at cost, taking no profit whatsoever.

When Armistice day arrived and the war was finally over, Kimberly-Clark found it had partially filled orders for 750,000 lbs (over 340 tonnes) of Cellucotton and in another altruistic act Kimberly-Clark allowed these orders to be cancelled without penalty.

It left the company with a huge surplus. Worse still, the Army also had a large surplus of Cellucotton – and they began selling it to civilian hospitals at a ridiculously low price, instantaneously killing the market for Kimberley-Clark.

The better news for Kimberley-Clark, and perhaps one small contributing factor to their generosity, was that word had got back to them about an alternative use for Cellucotton. Not long after its first arrival at the battlefields that a completely unexpected use was found for some of the bandages.

The female nurses and the nuns tending the wounded started using it for their “Lady Days” (as periods were referred to then), it was after all five times as absorbent as cotton and so was much better and more hygienic than the pieces of rags which they had been using previously

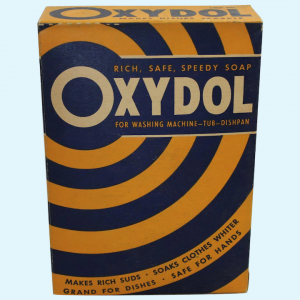

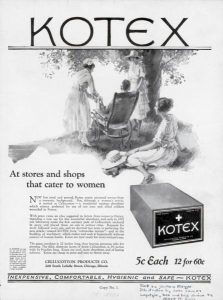

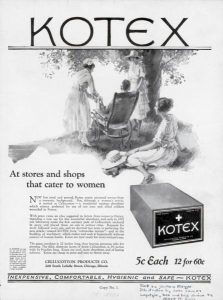

Kimberley-Clark decided to try and market them to women as feminine hygiene pads. They were rechristened Cellunaps (cellucotton – napkins) and positioned to retailers as the first disposable sanitary napkin.

Kimberley-Clark however had to find their way over another barrier. Retailers, though seeing the potential, were worried about public sensitivity and many women were not happy to ask the mostly male assistants for them at the counters.

Sales did not go well.

Kimberley Clark decided on a new approach.

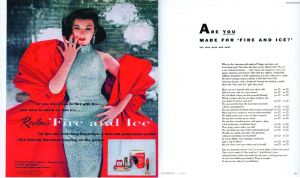

They changed the name to KOTEX, a meaningless word merger of c[K]Otton-like TEXture that would hopefully not reveal anything in a crowded drugstore. The second and perhaps crucial change was the introduction of counter displays so that women could buy their Kotex without talking to the clerk. At the time this was not something that every retailer immediately agreed to, but as results were soon to show it solved the problem of a product people didn’t want to really talk about, and definitely didn’t want to ask a member of the opposite sex for.

As counter and shelf displays grew so did the sales and the brand.

What are the implications, if any for brands?

At the moment when there are still shortages of so many medical essentials it is difficult to make any concrete predictions but it maybe that marketers will need their ingenuity to re-purpose hand sanitizers, PPE and even ventilators. Alternatively they may want to explore any opportunities that arise for future utilisation of their new capabilities to move into different sectors.

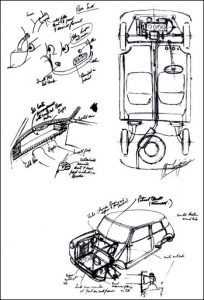

For example, a number of the large automotive companies who could probably use some long-term diversification strategies might want to look at Medtech opportunities, and Dyson is another obvious candidate to do this as The James Dyson Foundation has already made significant investments to support the advancement of medical research, as well as regular donations to medical research charities.

Footnote : As Kotex sales began to grow, letters started to pour in to the company, mostly favourable but many were from women who wanted to know more about their bodies and the menstrual process. As a result Kimberly-Clark built its Education Division and began mailing out information packs, including a pamphlet called “Marjorie May’s 12th Birthday” which was initially banned in some states for being too sexually explicit.

Later they were to work with the Disney Company to create a movie called “The Story of Menstruation” which would be shown in schools and was seen by over 70 million schoolchildren – a most unlikely most-watched movie from the Disney catalogue.